ENHARMONIC MODULATION - THE ULTIMATE GUIDE

Hello reader, and welcome to beethoman.com! Enharmonic modulation is one of many possibilities regarding a change of tonal center (key). After reading this material, I hope that you’d be in a position to do your homework, paper or thesis (or whatever you’re doing actually), and to understand the principles that stands behind this type of modulation.

BASIS OF THE ENHARMONIC MODULATION

If you’re stuck with enharmonic modulation, then you have probably already faced the concept of modulation in general. Diatonic modulation for example, “the simplest kind of modulation” is actually very similar to enharmonic modulation. Musical flow migrates from one tonal center to the other by one chord that is mutual to the both tonal centers (well, kind of mutual in case of enharmonic modulation). However, there are some significant differences that separate these two types.

While diatonic modulation is possible only if musical flow uses major or minor diatonic triad chords, enharmonic modulation cannot be possible without using seventh chords, or augmented triad chords. That’s the first big difference. The second one is that diatonic triad chord, major or minor, stay exactly the same in both tonal centers. In enharmonic modulation at least one note of used seventh or augmented triad chord must be changed enharmonically. What does it mean? Well, it means that one the notes must be transformed into its enharmonic counterpart. It will sound exactly the same, but it will be written differently. For example, if we have a diminished seventh chord e – g – b-flat – d-flat, it is very likely that note d-flat will be transformed into c-sharp (Example 1). And that, my dear reader, is the essence of the enharmonic modulation. These two notes are enharmonically equivalent.

TYPES OF THE ENHARMONIC MODULATION

Like diatonic and chromatic modulations, enharmonic modulation also may have multiple possibilities regarding the type of chords that will be enharmonically processed. There are three distinctive chord shapes used in a music history for a purpose of enharmonic modulation. First is diminished seventh chord. It is arguably the most “popular” in music literature of all three. Second is dominant seventh chord. Its enharmonic counterpart is very interesting as we shall see in a moment. Very popular, especially in romanticism. And third is augmented triad chords. Heaving that said, let’s break these chord shapes into their basic components and ultimately explore their usage in some remarkable musical pieces of 18th and 19th-century classical music.

ENHARMONIC MODULATION BY USING DIMINISHED SEVENTH CHORD

Diminished seventh chord is one of the most powerful tools in music. It is almost like a musical chameleon. It can change its pigment (enharmonic inscriptions) so it can blend in so many different contexts (tonal centers). That unique trait derives from its unique structure – three minor thirds, one on top of the other. No matter which inversion of that chord we use, the distance between notes will always be the same – minor third. Because of that, a single diminished seventh chord could be found in four different tonal centers (keys), representing the exact same function, regardless of their remoteness.

Combining different functions between tonal centers opens even more possibilities. So, let’s have a look at this “chameleon”. Diminished seventh chord is often related as a leading tone chord, so we will use this in our example (Example 2). For the sake of visual clarity, all variants will be written enharmonically equal. It will produce different chord inversions in different tonal centers though, but, essentially, it is the same chord.

At the end of 11th measure, the musical flow is still in original key (tonal center) of A-flat major. Function VIV7 is preparing the subdominant function, but the next chord in 13th measure brings a surprising development. It is a diminished seventh chord on the altered (sharp) ii (note) of A-flat major – b(natural) – d(natural) – f – a-flat. Its analytical designation is #iio7. Now, we can see that music flow is changing in the following measures, so our next step should be to identify the new tonal center (key). Resolution of tension appears to be in 17th measure in B major key.

The next step should be to find logical place to execute the modulation. Because we already have diminished seventh chord in 13th measure, we should try to examine the possibility of enharmonic exchange. Two notes out of four in #iio7 of A-flat major can be found in B major as well – d and b. But notes like a-flat and f cannot. They have to be enharmonically changed into g-sharp and e-sharp. Now, our enharmonically changed chord looks like this – g-sharp – e-sharp – b – d. It is the first inversion of diminished seventh chord e-sharp – g-sharp – b – d, which constitutes #ivo7 diminished seventh chord in B major. Its resolution is quite a typical practice involving V6/4-5/3 and I to settle the harmonic tension down (Example 3).

ENHARMONIC MODULATION USING DOMINANT SEVENTH CHORD

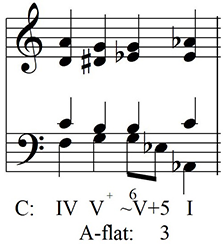

Enharmonic modulation using dominant seventh chord is an exclusive product of harmony in the Romantic era. Uniqueness of this modulation lies in the fact that this procedure is much, much more than just a key change. It affects musical expression on such a profound level, like no other type of modulation, completely changing the emotional line of a piece. That trait derives from the very nature of this modulation and the chord shapes it uses for its execution. Earlier, as we saw, both chords used in a modulation were diminished, but now, things are quite different. If we have dominant seventh chord in original tonal center, its enharmonic counterpart in the following key will be double diminished seventh chord (German sixth chord, always in 6/5 position). Amazing, right? Let’s take a look at one example of this modulation (Example 4).

The main stars of this show are V7 of C major and #ivo6/5 (German sixth chord) of b minor. V7 is a simple dominant seventh chord, but its structure can be enharmonically changed into German sixth chord 6/5. All we have to do so we could be in a position to see this in a musical flow that we analyze is this: 1. follow the direction of melody and harmony to find the new tonal center; 2. check for possible chords that can be used for modulation; 3. double-check if enharmonic exchange is analogous to previous V7 chord; 4. execute the modulation.

Because of that sudden change, where already reached dominant seventh chord enharmonically reestablish itself as a chromatically altered chord of #IV, a huge emotional shift occurs in a musical flow. Our expectation of resolving tonic function is completely deceived, and that’s pretty much the main reason why this type of modulation is such an easy one to hear in a musical flow. Listen to it in the following video (until 8:33).

This section is actually a continuation of phrase we used in Example 3. As we can see musical flow is still in B major at the start of 24th measure. A slight digression – note how casually that dominant seventh chord with augmented 5th were used by Liszt at the end of the first measure in our Example 5. Now, let’s get back to our business. Pay attention to measures 25-27, where we can see the enharmonic exchange of B major tonic chord. At the beginning on 27th measure c-flat is actually b-natural; e-flat is d-sharp; g-flat is f-sharp and that b-flat note, marked with a green circle is a simple passing tone.

Modulation occurs in the next measure, yet enharmonic exchange is preparing us for a new development in a musical flow. Now, in 28th measure the real thing is going on. What would be a VIV7 in B major actually is German sixth 6/5 chord in E-flat major. It is written only as a German sixth 6/5 chord, simply because it is easier to understand it in the new context that musical flow gets in these measures. That is one thing that we should be very aware of – in actual music, alike in school exercises, enharmonic modulation will not have both inscriptions, but very likely only one that represents the tonal center (key) where musical flow is going to.

Another way of doing it

However, there is one more possibility to modulate enharmonically with the chord that has minor seventh in its structure. As dominant seventh chord has it, for example. But, things are little different now. It is a dominant seventh chord with diminished 5th. In the moment of modulation that chord is in its root position (7), but after it is enharmonically exchanged it changes its position to 4/3 – French sixth chord. Basically, it is a second inversion of the dominant seventh chord with diminished 5th.

Now, both chords are essentially the same, but the chord in new key must be in 4/3 position. It is interesting that distance between two keys will always be a augmented fourth (tritone) when this type of modulation is used. Here is one example of this kind of modulation (Example 6). It is almost impossible to find this kind of modulation in actual music. When I find it, I will definitely write a post about it. If you find it, please share that discovery with us. 😊

ENHARMONIC MODULATION BY USING AUGMENTED TRIAD CHORDS

Last, but not least is enharmonic modulation by using augmented triad chords. Like most part of enharmonic modulation, this type is also one of the main characteristics of romanticism. Augmented triad chord can be found in four distinctive places:

- iii+ triad chord in minor key;

- V+ (with augmented 5th) triad chord in major key;

- (flat) VI+ triad chord in harmonic minor key;

- VIV+(with augmented 5th) triad chord in major key.

Enharmonic exchange includes one or two notes of the chord. Every note of any augmented chord can become a root note when modulation occurs. Therefore, this type of modulation potentially lead musical flow to 9 keys (3×3). Since these are triad chords, one must be very aware of voice leading. This topic will be specially covered in some other post. Here’s one example of this type of modulation (Example 7).

Example 7

Music literature also gives us fine examples of this modulation type. One of them could be found in Chopin’s Sonata in B-flat minor (I movement). Let’s take a closer look at that event (Example 8).

Example 8

Modulation by using augmented triad chords is crystal clear. Musical flow uses one augmented chord that is common for both keys. However, there’s one other thing. Note the moment of modulation from B-flat minor to B-flat major right before the end of our example. Now, these keys are parallel and quite related. But, that #IIo7 can’t be found in B-flat minor simply because C sharp is already D-flat which is a natural iii in B-flat minor key. Therefore, one chord has two different functions in such a related keys while sound stays exactly the same. One should be aware of this – in regard of its resolution its sonority will create a different context. And that’s the beauty of music.

I really hope that this post will help you understand and comprehend enharmonic modulation. If you have some specific question or idea about what should I write in the next post please tell me in the comment. Or contact me privately. Feel free to share this post to your friends if you think it will help them. Until the next reading good luck!

Subscribe to receive new posts once per month. It is completely free!